Learning to be tooth carpenters

History of dental education in Queensland

Today's graduands from Queensland dental schools prepare to enter a profession vastly different from that encountered by young dentists in the past. For the last century, the only constant has been the rapidity and impact of the changes in technology and scientific knowledge, with dental schools tasked to both drive and catch up to these developments.

Here is a brief retrospective on 100 years of dental education in Queensland.

IMAGE 1: Cover of Illustrations of Regional Anatomy textbook, 1956. ADAQ Archives. 2: - Queensland College of Dentistry Final Students Photo 1933

The concept of formal education at a dental school is another eighteenth century ‘illumination’. After Pierre Fauchard laid his principles of modern dentistry with Le Chirurgien Dentiste (1728) and John Hunter published Natural History of the Human Teeth (1771), dental colleges appeared in Europe and the established knowledge in this new ‘vital science’ started to circulate.

Until then, young men in most Western countries had learned the skills of ‘toothdrawing’ and denture making as apprentices to apothecaries, surgeons or barbers, for whom dentistry was only one of the many services they offered.

The first dedicated dental schools appeared in Baltimore (1840) and London (1858). In England, the Medical Act of 1869 formalised the registration of authoritatively trained dental licentiates.

In Australia, the first dental college was first established in Melbourne in 1892. Dental Acts were passed only at the turn of the century.

Here in Queensland, the barber-surgeon era was not truly over until the Dental Act was passed in 1902, with provisions to establish a Dental Board to control examination and registration of dentistry.

This means there was no recognised minimum training until 1902, and no control on practice or ethical behaviour: nothing to prevent anyone from opening their own premises and make public claims about their skills in relieving pain and fixing teeth issues.

A technical pursuit

Dentistry shaped itself as a distinct profession in the late nineteenth century, however it was still viewed as a technical pursuit rather than a natural science and it would be for the early decades of the twentieth. This is understandable: operative and prosthetic dentistry constituted the bulk of expertise required to set up practice.

In the Jubilee History of Queensland publications of 1889 and 1910, dentistry is still listed in the manufacturing industries section, among mining and printing:

In fact, throughout all the Australian colonies technical education has received much attention within the last few years and is made part of the educational policy of the respective governments […] Numerous classes have been formed in mathematics, engineering, mining, assaying, analysis, chemistry, farming, dentistry, photography, engraving, printing in all its departments, agriculture, etc. Who would have thought that almost 150 years later, dentists would do actual printing, although in 3D machines!

(p.343, Jubilee History of Qld 1889.)

Indentures...For making dentures!

The first formally trained dentists to set up practice in Queensland had completed their apprenticeships in Britain or the United States, where dental schools had already been established. Many were members of the Royal College of Surgeons (Diploma of Dental Surgery, holding the postnominals: LDS – Licentiate of Dental Surgery).

They had enormous influence in the development of dentistry and dental schools in Queensland. For example, David R Eden, first president of the Odontological Society of Queensland, after setting up practice in Brisbane, in 1866, was master to many dentists who later became respected names in the state’s dental education and professional associations.

With modern eyes, the apprenticeship system can be easily seen as an elitist and inefficient institution that impaired the free circulation of knowledge and new techniques. However, as Bishop et al. pointed out in their 2002 paper on the development of professional ethics in dentistry: The scheme […] had a positive influence on the morality, legal identity, and professional allegiance of dentists during the ethical development of their profession in the nineteenth century

The standard wording from surviving indentures held by the British Dental Association’s archives, reveals how the Master was expected to cultivate his pupil’s morals and social manners:

"….at cards, dice or any other unlawful game he shall not play…He shall not haunt ale houses, taverns, play houses, or any other places of debauchery…

(Indenture LDBDA 1868, 06.7, cited in Bishop et al., 2002)

The curriculum was at the discretion of the Master, and only he decided whether the apprentice had reached sufficient skills to practice on his own. However, a professional esprit du corps was evidently fostered over the generations. It matured starting late 1800s into the creation of professional associations worldwide, and later, into the structured education and practical tuition in tertiary schools.

ADAQ holds a much later Deed of Apprenticeship, signed in 1925 for two years training required at the time. It documents the gradual change from the four-year apprenticeship system to a university qualification, with many students passing through a mixture of apprenticeship and service at an approved Dental Hospital or school to acquire ‘professional knowledge’.

Wagner’s indenture document. 1925. ADAQ archives.

School of Dentistry

Queensland stood out among the other Australian states in that a course of study in dentistry was established before medicine, and not within the medical school as in most universities at the time.

The first university in Queensland was established in 1909. Dental training was a collaboration with the University of Sydney for the medical subjects, and included Chemistry, Botany and Zoology. Two years of practical work followed this formal tuition

The Brisbane Dental Hospital, established by the Odontological Society in 1908 initially for those who could not afford private treatment, introduced apprentices who completed their two-year practice there. In 1914 it was recognised as a teaching institution, and in 1926 it was taken over by the Home Office, with dental education now controlled by a Joint Board of Dental Studies. A faculty dedicated to dentistry was established in 1935 (Lumb, 1950)

The Government offered the Westbourne residence in George Street for a new expanded facility that catered for students (1916). Students in the final two years were assisted by thirty honorary demonstrators on a rotating system.

The Brisbane Dental Hospital on George Street, 1917. State Library of Queensland.

The dentistry subjects as listed in 1925 were:

- Year 1: Physiology and histology, osteology, dental anatomy and histology, dental metallurgy, practical anatomy demonstrations.

- Year 1 and 2: Dental materia medica and therapeutics, operative dentistry, prosthetic dentistry, anaesthesia, radiography.

-

Year 2: Bacteriology and pathology, orthodontia, crown and bridge work, cleft palate work, dental jurisprudence and ethics, oral hygiene and prophylaxis, office management.

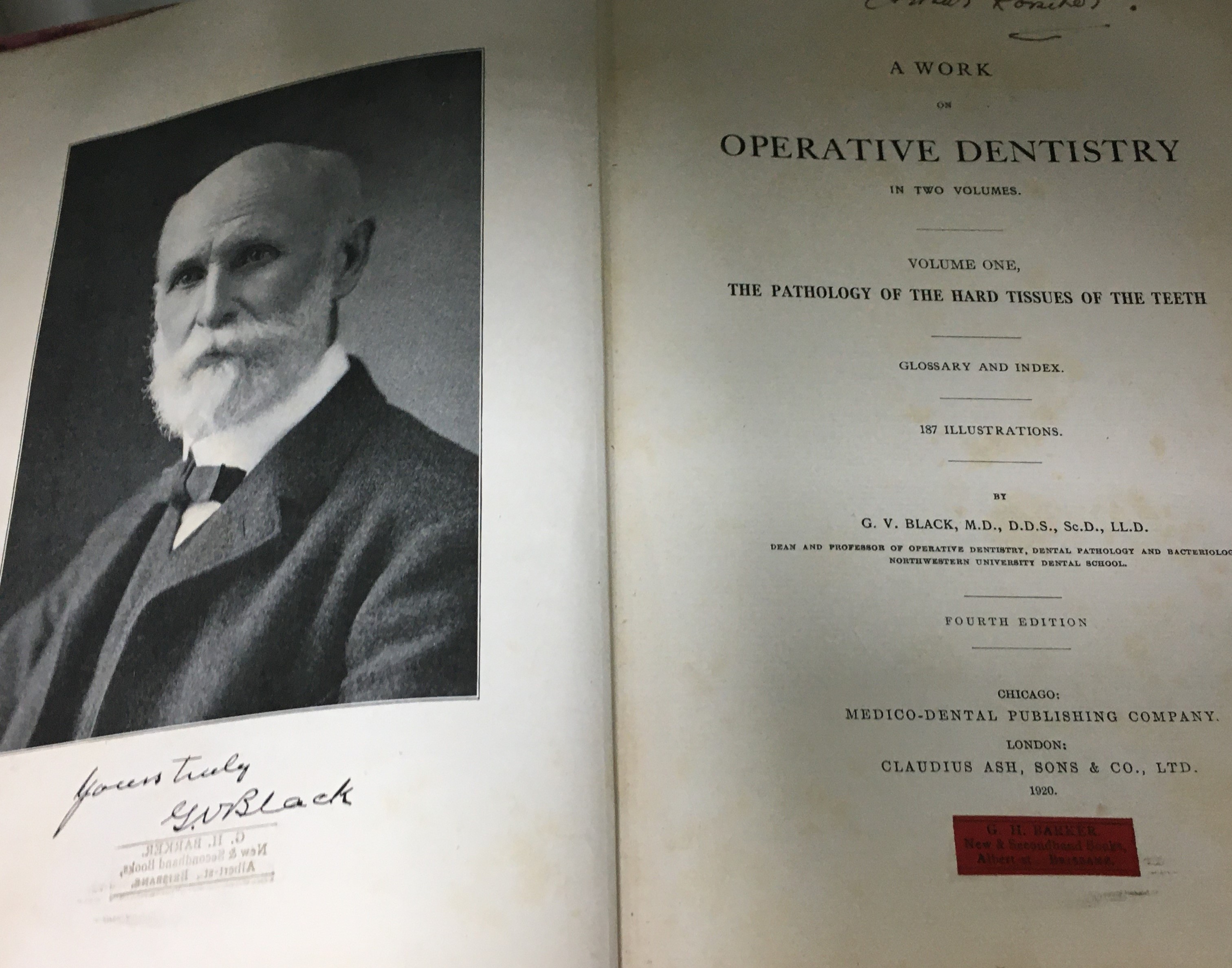

GV Black’s Operative Dentistry, 1920. Signed by yours truly [Black]. ADAQ MoD. Black’s caries classification has haunted students for over 100 years...

In 1926, the private apprenticeship system was entirely abolished: students would attend the College of Dentistry for the full four years and the Dental Board only dealt with registrations.

Entrance to dental school required passing the matriculation exam with English, a language other than English, Mathematics I, Chemistry and Physics.

The focus on technical and mechanical skills remained. In 1933, Year III students were required to perform: 18 dentures, 230 amalgam operative dentistry and 30 gold inlays, and 40 cases of periodontics (Marlay, 1979).

However, an educational shift from craftsmanship towards theory and science soon followed, and defined the second half of the twentieth century, as well as the introduction of specialist registration.

In 1962, there were 696 dentists registered in Qld, of whom 42 were also registered as specialists (1962 Calendar of the Dental Board of Qld, ADAQ Archives).

Gold inlay student demo on plaster, 1950s. ADAQ MoD. Students had to demonstrate their achievements in restorative dentistry.

Flexible learning

Between 1936 and 1971, the Bachelor of Dental Science was remodelled, with: An increased emphasis on basic sciences and on preventive/community dentistry, and a decreased emphasis of (…) exodontics and prosthetic dentistry (Kruger, 1976).

From 1972, further changes included the introduction of shorter semesters and standard units of credit, greater flexibility in clinical subjects and a variety of electives:

Every student […] should feel that he was in a world of possibility, where nothing was completely resolved, and he should come to acquire the excitement, almost innocence, of an inquiring mind. That chance may never come again. But if he achieved that quality as a student, it would be with him and influence his thoughts and action thereafter (Kruger, 1976)

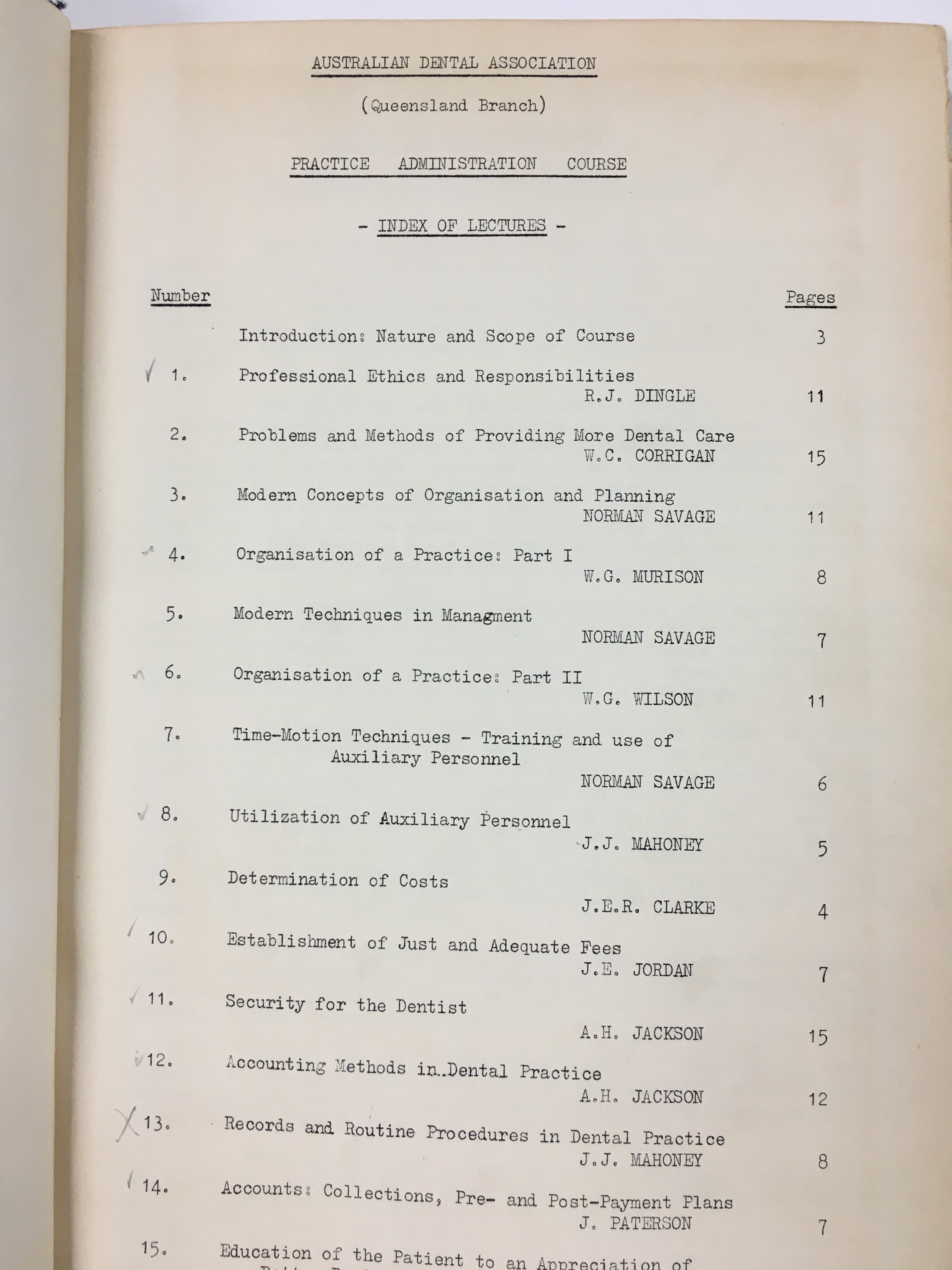

ADAQ’s Practice administration course – contents page, 1950s. One of the ways the association helped new dentists be a success.

The Millennial Dentist

At the 24th Australian Dental Association Congress in May 1985, Professor KF Adkins, Dean of the Faculty of Dentistry, UQ, delivered an address as a tribute to the Golden Jubilee of the Faculty. Adkins predicted that, at the turn of the new millennium, dentists would deal with an older, more urbanised, and ethnically mixed Australian population.

Somewhat prophetically, he anticipated that these millennial students would be well trained in: “the social and behavioural as well as the biological factors” and would be increasingly: “accustomed to accessing information via the video systems and programmes of computer assisted learning”.

Moreover, Adkins foresaw significant increases in the time devoted to periodontics, orthodontics, clinical pharmacology, and oral medicine, and less to restorative dentistry (Adkins 1985), and speculated that dentistry could (or should?) still revert to being part of medicine with post-medical training programs. In summary, dentists would have a complicated and much-expanded role in the future.

In his predictions, however, he did miss some important developments, namely the post-1980s rise in the number of female and culturally diverse dentistry students.